A Generation of School Choice - Part 2: The Exodus That Wasn't

- Jim May

- Jun 17, 2024

- 9 min read

Updated: Jun 24, 2024

In early 2011, on the eve of the Indiana General Assembly beginning to siphon billions of public dollars to private schools, the results of two separate surveys were released pertaining to school choice.

The first, conducted by IU’s Center for Evaluation and Education Policy, found that only 6.5% of Hoosiers approved of the state adopting vouchers to funnel money from public schools to their private counterparts.

The other, performed by the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice, now known as EdChoice, claimed that 41% of parents would transfer their kids to private schools if they could.

Obviously, our legislators chose to discard the former and embrace the latter.

We Paid How Much to Increase Private School Enrollment by How Much?

If you’re a parent, educator or simply an informed Hoosier, you’re likely familiar with some aspects of how the intervening years have played out.

Even our legislators, though they may not openly voice their culpability, admit the detrimental effects of their policies through their actions. When they do things like lowering standards because schools can’t afford skilled personnel or implementing draconian retention mandates because they claim we’re in the midst of a literacy crisis, what they’re really doing is admitting they have failed our children and our communities.

But did they at least get what was promised? Did EdChoice’s propaganda hold true in full or in part? If 41% of public school parents moved their kids to private schools, today we would have around 46% of kids in private schools, with 54% in public.

Let’s take a quick look at enrollment over the past 15 years.

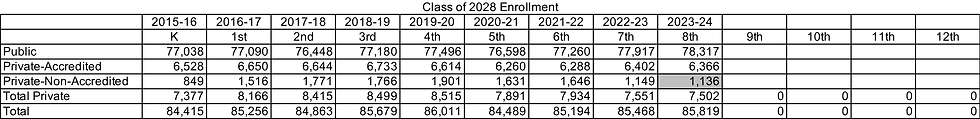

When graphed, it can be difficult to even tell if the percentage of kids attending private schools has changed at all. Here’s the data in a pair of tables, to make the shift a bit easier to digest. Note, the gray cells are estimates. If you’re curious about why that’s necessary, I’ll cover it in the last section of this article.

That’s right. The needle has moved from 92% of kids attending public schools, all the way down to a mere 91%. I’m not sure how one would determine how much of that change can be attributed to spending taxpayer money on private education, but let’s assume it was all of it. How much did we pay to move where 1% of students attend school?

Let’s add annual state spending on SGO and Choice scholarships to our previous graph. It’s the pink line. Note that it’s on a scale of $0 to $600,000,000 annually.

That’s just under $2.3 billion total. While that’s not a bad return on investment for the privatization lobbyists who spent millions to buy policy, it’s a pretty poor one for the taxpayers who have had to foot the bill.

Hundreds of Families Aren’t Pulling Their Kids From Your Local Public Schools

This election season, you will almost certainly hear a claim from school board candidates backed by Moms For Liberty and other, similar anti-public-education groups. It’s the lie that started me on my own journey of public school advocacy when I saw school board candidates making it in our local election in 2022.

“Hundreds of families have pulled their kids from our public schools and are choosing private schools instead.”

This is, quite simply, not true. But it gets repeated. A lot.

The PACs pushing for privatization LOVE to repeat it. In turn, it gets picked up and repeated by local and national media. Just this morning, the New York Times’ daily enewsletter reported on the falling number of kids attending public schools, citing a report from EdChoice, the last source anyone should take at face value when it comes to K-12 school data.

Earlier this year, parents of a neighboring school district reported that their superintendent made such a claim, saying he was going to personally reach out to the families of 1,900 students who had left the district to try to get them to come back. Except, there aren’t 1,900 students who left their district. A realistic estimate would be fewer than 100, and it’s impossible to say how many of those actually went to different schools as opposed to simply having their families move.

So where do these overblown, exaggerated numbers come from? How do they obscure actual data and lead even seasoned journalists to report disinformation as fact? In Indiana, it boils down to the word ‘transfer’ and how our Department of Education has chosen to redefine it.

Let’s Talk Transfers

When a normal person talks about transfers, they’re referring to something moving from one place to another. Not so for the Indiana Department of Education.

Say you give 100 people a marble and ask each of them to place their marble in either an orange bowl or one of two blue bowls. Anyone can put their marble in the orange bowl, but when it comes to the blue bowls, people with a household income of over $100k put their marble in the dull blue bowl and people with a household income under $100k put their marble in the bright blue bowl. After everyone places their marbles, the distribution looks like this.

A year passes and someone asks you to report on how many marbles have been transferred from the orange bowl to the blue ones. You look at the bowls and nothing has changed. They still look like this.

You, as a normal person with an understanding of the English language, would almost certainly say, "No marbles have been transferred." The Indiana Department of Education would say one marble has been transferred from the orange bowl to the blue ones.

Another year passes. The rules change for the blue bowls. Any marble that was placed in the dull blue bowl by a family making less than $150k is to be moved to the bright blue bowl. At the end of the year, you’re asked again to identify how many marbles have been transferred from the orange bowl to the blue ones. Because of the rule change, three marbles have moved from the dull blue bowl to the bright one. The same 92 marbles are still in the orange bowl. It looks like this.

You, still being a normal person with an understanding of the English language, would likely say, "No marbles have moved from the orange bowl to the blue ones." The Indiana Department of Education would say four marbles have been transferred from the orange bowl to the blue ones. Groups like EdChoice would then issue press releases saying that the number of marbles transferred to blue bowls quadrupled that year. Reporters would write stories about how there’s a trend of people moving their marbles from the orange bowl to the blue ones.

That all happens due to two quirks in how Indiana reports on 'transfers'. First, any student attending a private school is considered a transfer from a public school, even if they've only ever attended the private one. Second, the state only includes data on students who qualify for Choice Scholarship vouchers. So when our legislature makes wealthier people eligible for vouchers and more people use them, the Indiana Department of Education reports more transfers, even if not a single student changes which school they attend that year.

As a result, the data reported by the state has little-to-nothing to do with the number of students who have actually left their public schools. As we'll see from enrollment data, we always have 7% - 9% of students attending private schools. We know that at least around 70% of those have never attended a public school. Yet, the state still reports them as 'transfers'. And when more of them qualify for vouchers, the state shows we have more kids 'transferring' out of public schools.

Put simply, we could have had zero students move from public to private schools over the past thirteen years, and the definitions and reporting methods of our state would still create the impression that many, many had, just from marbles moving from the dull-blue private-school bowl to the bright-blue private-school bowl.

So How Many Kids Actually Moved From Public to Private Schools?

The short answer is, due to the level of detail in the data collected by and reported by the state of Indiana, it’s impossible to say. We can be quite confident, however, that far fewer parents have moved their kids from public to private schools than is conveyed by local reporting. We can also be absolutely certain that it’s a very small fraction of what can be found in past propaganda and current spin by pro-privatization PAC’s like EdChoice.

I struggled with how best to report the mountain of enrollment data I’ve collected, sifted through, cleaned up and organized. I’m opting to share it broken down by cohort, as I think that makes it easiest for someone to make sense of it. So here we go, starting with the one year available for the Class of 2036 and going back to the Class of 2021. Why 2021? Because that cohort was in kindergarten in 2008-09 and that’s the first year for which we have enrollment data on non-accredited private schools. Sorry, these are going to be tough to read if you're visiting on your phone.

What’s that tell us? Well, if we spend some time looking at it, it appears that, following the 2019-20 school year, slightly more parents are giving private schools a shot in the early elementary years. But not a dramatically higher number.

Consider the Class of 2032 and younger: each of these currently have more kids than ever enrolled in private schools, but the growth is mostly small. Additionally, current 2023-24 private school enrollment for any given grade is more on par with previous peaks as opposed to surpassing them.

Another way to look at the data is by expected via actual enrollment. In this case, expected enrollment for each year is calculated by taking the previous year’s total enrollment, adding the current year’s number of kindergarteners and subtracting the previous year’s number of seniors.

One interesting point is that we see demographic changes accounting for a decrease of ~23.5k students since the 2018-19 school year. Over that same time period, the number of private school students increased by ~3.5k, leading to a total decrease in public school students of ~28k. Put another way, for every decrease of 8 students in public schools, 7 are due to changing demographics and 1 is due to more people experimenting with sending their kids to private schools.

One other important factor to keep in mind when looking at expected vs actual enrollment is the impact of people dropping out of high school. That rate has improved over the years, which accounts for some of the trend of expected and actual public-school enrollment moving closer to converging.

There’s something else to consider as well…

More Families Than Ever Are Pulling Their Kids From Private Schools

As part of its annual Choice Scholarship program results, the Indiana Department of Education includes figures on the number of voucher recipients who leave their private school midyear. While the state has only provided that data through the 2022-23 school year, it’s definitely worth considering.

So, when we note that an increasing number of parents are experimenting with private schools, we should also note that a lot of them seem to be unhappy with the results. If we assume that those withdrawals end up enrolled in their local public school, it makes our legislature seem even more ineffective and wasteful for spending $2.4 billion of taxpayer money to push kids towards private schools.

Of course, it’s likely that at least some of the parents who pull their kids from private schools re-enroll them at other private schools or switch to homeschooling, but the growing number of mid-year withdrawals is worth noting regardless. The state won’t provide 2023-24 withdrawal numbers for nearly a year, but given the record expansion of the voucher program for the past school year, it will be very surprising if we don’t see a corresponding record number of withdrawals.

Some Caveats to Close

I’ve done my absolute best with the data, but Indiana does not make it easy. Here are some of the larger hang-ups I ran into:

Charter school enrollment data isn’t included for the 2013-14 and 2014-15 school years in the reports on the IDOE website and has to be requested from IDOE.

Accredited private school enrollment data is lumped in with public school reporting for 2005-06 to 2009-10, but then gets its own, separate report starting in 2010-11.

Non-accredited private school enrollment data isn’t on the IDOE website and has to be requested from the state.

Non-accredited private school enrollment data isn’t available at all for the 2009-10 or 2023-24 school years and the data set for 2014-15 is clearly missing a significant amount of K-8 enrollment.

There are many instances of private schools having their enrollment double reported, appearing in both the accredited and non-accredited data sets. This was most egregious in 2010-11 and 2011-12, though it occurs sporadically through other years as well.

Making the data as reliable as possible required a lot of manual work, comparing reporting for both accredited and non-accredited private schools, year-by-year, school-by-school to remove duplicates.

I also had to use estimates of non-accredited private school enrollment for 2009-10, 2014-15 and 2023-24. I filled most of those data points with simple averages based on cohort. For example, the non-accredited private school Class of 2023 included 1,669 students in 3rd grade (2013-14) and 1,598 students in 5th grade (2015-16), so I averaged those and assumed it had 1,634 students in 4th grade (2014-15).

It was a bit trickier to estimate kindergarten and 9th grade data for those years. Kindergarten is obviously a challenge because it’s the first year many students enroll. The difficulty with 9th grades stems from the fact that a significant percentage of parents sending their kids to private schools shift to public schools for high school. To estimate those specific numbers, I adjusted previous and/or following years by the average historic growth rates.

In short, my data set’s not perfect, but unless the state has untainted data that it withholds from the public, I feel comfortable saying I’ve compiled the most accurate estimate of Indiana school enrollment data that exists for the 2009-10 to 2023-24 school years.

The data for this article comes from the Indiana Department of Education, including its annual enrollment reports, annual Choice Scholarship program reports, annual SGO program reports and additional charter school and non-accredited private school annual enrollment data provided by the department upon written request. If you have any questions or think you've spotted an error on this page, please send me a message through contact me page of the site.

Comments